By Andy Wong

Launched and promoted to great fanfare by the ruling party, the progressive wage model looks good as a press release, but is hamstrung by the twin flaws of obviousness and impossibility. Obviousness, in the sense that it describes a relatively straightforward career progression ladder that employees should be encouraged to climb toward greater salaries – an idea that many would suggest does not require a million dollar minister to think up. But also the impossibility of the system is glaring, because there appears to be no way to actually require employers to give their staff the chance to climb this skills ladder. In fact, one look at an example “wage ladder” reveals another truth which should have been obvious – a company staffed with employees who have all reached the highest rung would be very “top-heavy” and probably unsustainable as a business.

Launched and promoted to great fanfare by the ruling party, the progressive wage model looks good as a press release, but is hamstrung by the twin flaws of obviousness and impossibility. Obviousness, in the sense that it describes a relatively straightforward career progression ladder that employees should be encouraged to climb toward greater salaries – an idea that many would suggest does not require a million dollar minister to think up. But also the impossibility of the system is glaring, because there appears to be no way to actually require employers to give their staff the chance to climb this skills ladder. In fact, one look at an example “wage ladder” reveals another truth which should have been obvious – a company staffed with employees who have all reached the highest rung would be very “top-heavy” and probably unsustainable as a business.

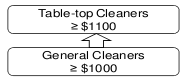

No more general cleaners?

The example progressive wage ladder for F&B establishments at the right is taken from an MOM press release, and it highlights some of the flaws with the progressive wage model. Are employers actually required to allow staff to climb the ladder? If so, I predict an imminent shortage of general cleaners as everyone suddenly upgrades to be a table top cleaner. If not, the whole scheme looks quite pointless. But if staff are automatically allowed to move up, the obvious outcome is that everyone goes for the 60% pay rise to become a supervisor, which is clearly unsustainable. A cleaning company cannot survive with only a team of supervisors and no actual cleaners, so there must necessarily be restrictions on the “who” and “when” of progress up the ladder. But, surely companies already have their own organisational structures, with general cleaners, table top cleaners, supervisors and all the rest of it, and then, where will the opportunity to move up the ladder actually come from? Is progress up this ladder not dependent on someone higher up leaving or retiring? If so, then what is the wage ladder actually describing? Is this organisational structure, and this scope for moving up the hierarchy not actually how every business is already run today? Is this not the existing process by which any current cleaning supervisor came to be where they already are? Unless the purpose of the progressive wage model is to restructure companies and force them to be more top-heavy, there doesn’t seem to be anything intrinsic to the wage ladder which creates new higher-paid opportunities. Everyone is stuck waiting for hypothetical chances to advance which may never materialise.

Despite the concern that promotion and seniority may be acquired perhaps no more quickly under the progressive model, there is still a glimmer of hope. Should we not be grateful for the salary benchmarks set out along the way? $1,100 is not bad for a table top cleaner, no? $1,600 for a cleaning supervisor? Unfortunately not, and this brings us to the second problem with the progressive wage model. The salaries depicted are for the most part only suggestions, and even then, the whole ladder evaporates when we realise it is almost completely voluntary.

The unenforceable ladder evaporates

The progressive wage model has been promoted by the government as a superior alternative to a minimum wage. There is however one crucial difference between the two systems – legal enforceability. Minimum wages are typically legislated for, and paying below the minimum wage is illegal. The progressive wage model by contrast is voluntary and thus spectacularly unenforceable. Labour chief Lim Swee Say admitted as much to reporters in October:

“I can’t force them, right? I’m not the director of HR of all these companies”

[…] As the model relies on consensus, it can stall. And it did [in September], when two industry groups in the security sector baulked at the proposed $1,000 basic pay for guards – $200 more than the median.

Janice Heng And Toh Yong Chuan. Straits Times. 13 October 2013

In a country where the government is too weak to even require pay slips to be issued, why do we expect these “wage ladders” to be voluntarily adopted? It was reported that only 3 in 10 employers adopted the National Wage Council’s recommendation to give a 50 dollar pay rise last year. In light of this, the suggestion that employers will voluntarily rush to offer their cleaning staff the chance to upgrade, move up the ladder and thus increase their salaries is not tenable.

Voluntary actions aside, the government does have some leverage over employers. The wage ladder shown above was published alongside new accreditation requirements for the government’s “clean mark” scheme, and from April 2013 government contracts will only be awarded to accredited companies. So while this represents progress in one field, there are obvious gaps in industries that are not accredited or do not typically sub-contract to the government. Another glaring hole emerges when we look more closely at the details of accreditation:

Companies seeking accreditation are required to submit their company’s progressive wage structure, to demonstrate that they have in place a structure that enables their cleaners to upgrade and progress to their next respective wage levels. In particular, the structure would have to show that cleaners belonging to Group 1 and 2 receive basic wages beginning at $1,000 or higher

MOM. New Enhancements to the Clean Mark Accreditation Scheme (Annex B).

Surprisingly, when it comes to accreditation, the rungs on the ladder begin to evaporate. The mere existence of a ladder is now enough, and salaries of $1,100 for table top cleaners and $1,600 for supervisors have vanished. Only the lowest rung – $1,000 for general cleaners – is specified, and employers are apparently free to submit their own ladders with salaries much lower than what the government has recommended. Not for the first time, there appears to be a disconnect between what the government is bold enough to claim in a press release and what the legally binding black and white details actually say.

So despite the fanfare, there seems to be quite a few question marks around whether or not the progressive wage model can actually deliver. In fact, by linking accreditation and state contracts to the scheme, the government has apparently realised and taken steps to mitigate some of the issues arising from the essentially voluntary nature of the scheme. Yet, in attempting to mitigate such issues, the government only underscores the fact that a non-voluntary statutory minimum wage would surely be preferable. More fundamentally, the very essence of the progressive wage model appears to be flawed – requiring employers to define a wage ladder is one thing, the question of when and how employees can take steps up is quite another. For while the success of the ladder in raising wages appears to depend on allowing staff to step up, a company cannot allow everyone to step up, or else there will be no one left for the hoards of supervisors to supervise. So the underlying question of where new, higher paying opportunities will come from remains unanswered, and the lowest level workers are likely to be stuck in the same place they ever were, with the possibility but few chances to move up into higher paid positions.

The author blogs at http://andyxianwong.wordpress.com/