Timothy Tan

Why authoritarianism in Asia has met its death knell

In 1997, the American political journal The New Republic ran an article by Nobel laureate and economist Amartya Sen. In the article, bluntly titled Human Rights and Asian Values (1), Sen launched an unreserved attack on a concept which had recently gained currency – a concept then known as “Asian values”.

In 1997, the American political journal The New Republic ran an article by Nobel laureate and economist Amartya Sen. In the article, bluntly titled Human Rights and Asian Values (1), Sen launched an unreserved attack on a concept which had recently gained currency – a concept then known as “Asian values”.

First articulated in the mid-1990s at the height of an economic cycle, its foremost evangelists were our Minister Mentor, and former Prime Minister of Malaysia Mahathir Mohamad. Having emerged from a period of record growth in their respective economies, both leaders spoke from deeply fortified positions in regional and international politics. Deep enough, that they could afford to mount what sociology students might call a dialectical challenge: an alternative to the perceived hegemony of Western civilisation.

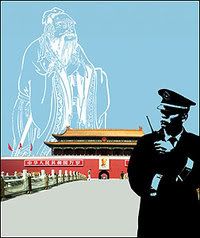

Returning to the article in question, Sen devotes a large part of his argument to examining the historical precedents, or lack thereof, that would point toward a unity of cultures and mores across the Asian continent. Not surprisingly, there is little evidence to support this claim. For instance, both Taiwan and Singapore have at one time or another appropriated the teachings of Confucius as part of national ethos, but toward vastly different ends and political outcomes: one to foster a blend of corporatism and paternalism within the state, and the other in support of civil discourse and an open political environment.

These conclusions are not news to anyone with the barest knowledge of history. Revealingly, a homogeneous Asia is actually an inherited colonial myth, reaching back to a period where countries either belonged to “the Orient” or “the Occident”. Also, such an artificial dichotomy conveniently leaves out the continents of Africa and South America – two continents which have been home to political systems of every imaginable stripe, from the dictatorial regimes of Zimbabwe or Sudan, to the socialist republics of Venezuela and Cuba, to the liberal democracies of South Africa or Colombia.

Amid all this misinformation, Sen places some of the blame, at least, on the parade of intellectuals in the Western tradition that have sought patent for every value and institution that makes up our present understanding of human rights. Ancient Greece and Rome, Sen reminds us, were cultures that openly endorsed slavery, sexism and racism – hardly a suitable candidate for the cradle of democracy. Contemporary Europe may have its human-rights monitors and commissions, but it was not too long ago that Fascism had marched into (almost) every corner of this continent, under the banner of Militarist and Nationalist values. Clearly, tracing the roots of democracy and human rights is more a question of when, not where.

But Sen demolishes a myth that is much less mundane, forcing “Asianists” – a term as inscrutable as it sounds – to finally admit their emperors are wearing no clothes. One may surmise, in fact, that “Asian values” has simply become the latest euphemism for autocracy and blatant disregard for the democratic process. The ideology co-opted by the state may be different in each case, be it Confucianism, anticolonialism, or ethnic pride, but the reality is that they are all ciphers. Ciphers that divert attention from the fact that what these “mavericks” (to borrow a catchphrase from Sarah Palin) want is their own brand of exceptionalism, in order to rationalise their resistance to accepted international norms. Which turns out to be really ironic, considering that exceptionalism itself is what the United States is often berated for.

While Sen does go on to give many more salient examples to support his argument, drawing from artefacts as disparate as the Indian classical epics and the religious profile of the Japanese, events and problems of more recent history give his thesis an empirical triumph. Though the ascendancy of the East Asian economies was halted by the financial crisis of the late 1990s, the old rhetoric did return as growth resumed and incumbents swept elections in Malaysia and Singapore.

But in cases like Indonesia, the opposite has happened. Despite repeatedly being on the precipice of civil war or economic ruin, its numerous political reforms in the last decade have brought national unity and steady economic growth. As unlikely as it may seem, with proportional representation and a free media, Indonesia is now the one member of ASEAN that most resembles a functioning liberal democracy. The Indonesian model is an especially poignant one for another reason. The democratisation process, far from being exacerbating instability in the wake of the Suharto era, has been a vital counterweight to radically divergent factions within Indonesian politics, between secularists and Islamist reformers, civilian and military interests, supporters of regional autonomy and those of centralised government.

A further blow to the case for a coherent Asian consensus comes in the form of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) rights. An emerging front in the modern human-rights movement, some consider it to be a solely Western preoccupation. However, in the year since our own Parliament voted to keep homosexuality illegal, Nepal’s Supreme Court ruled to overturn sodomy laws (2), while cities across India held inaugural gay pride parades. In Taiwan, presidential candidates debated same-sex marriage, and marchers marked gay pride in such proportions that would put many European cities to shame.

Here again, though, Indonesia is the surprise. Yogyakarta hosted an international conference of human rights experts in 2006 that culminated in the adoption of a document entitledYogyakarta Principles on the Application of Human Rights Law in Relation to Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity (3), which affirmed that GLBT rights involve not an expansion of human rights but an enforcement of pre-existing principles against all forms of discrimination.

Even in Malaysia, political realities have begun to chip away the monopoly of the ruling elite. Its social contract is now in tatters after landmark March elections, as multiparty democracy begins to take root. Once a bastion of so-called “illiberal democracy”, the ideology of its founders has apparently been unsustainable. Despite appearing insuperable, the ruling grand coalition became the victim of its own bloated excesses – steadily extending the powers of government while ignoring growing dissension within Malaysian society. Contrast this with another federated political system: that of the United States of America. Often a subject for political cartoonists, its tripartite system of government has nevertheless had remarkable longevity: weathering deep racial and class divisions, a Civil War, numerous political scandals and failed military campagns.

Yet, as support for the authoritarian model wanes throughout Asia, our government, primarily through its Foreign Service, has been trying to push the opposite case. In fora ranging from academic journals to press statements, our diplomats tirelessly refute the notion that democracy and development have any link at all. Often the response involves retreating behind a cringe-worthy combination of alleged Western conspiracy and neo-conservative posturing.

The most recent of these gaffes came in the form of an op-ed piece in the Straits Times (4) by former ambassador to the UN, and foremost disciple of the Lee-Mahathir doctrine, Kishore Mahbubani. After an obligatory round of West-bashing, the article made the bewildering claim that China was the world’s “most geopolitically competent” nation. China – whose actions in the international arena have often made it an easy target for activists and NGOs, who see the Chinese government as an enemy of freedom and human rights. Whose voting record in the UN General Assembly and Security Council has consistently been in favour of rogue regimes in Sudan, Myanmar and Zimbabwe. And whose exports are now synonymous with shoddiness and corruption, not least due to a tolerance of lax regulation, labour and environmental standards.

Back in 1993, Wong Kan Seng, speaking then as Minister of Foreign Affairs, was one of a handful of vocal objectors at the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna. In a perversion of semantics, he told assembled delegates that the “universal recognition of the ideal of human rights can be harmful if universalism is used to deny or mask the reality of diversity.” Apart from being a logical failure (should we then tolerate intolerance?), this kind of talk misses a larger point. No less than the equal dignity of each human life is enshrined in the language of human rights – one that exists regardless of cultural or geographical context. It is only when these universal truths are ignored, that the diversity of human expression and experience is truly in danger.

Back in 1993, Wong Kan Seng, speaking then as Minister of Foreign Affairs, was one of a handful of vocal objectors at the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna. In a perversion of semantics, he told assembled delegates that the “universal recognition of the ideal of human rights can be harmful if universalism is used to deny or mask the reality of diversity.” Apart from being a logical failure (should we then tolerate intolerance?), this kind of talk misses a larger point. No less than the equal dignity of each human life is enshrined in the language of human rights – one that exists regardless of cultural or geographical context. It is only when these universal truths are ignored, that the diversity of human expression and experience is truly in danger.

(1)http://www.brainsnchips.org/hr/sen.htm

(2) http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/7156577.stm

(3) http://www.yogyakartaprinciples.org/

(4) http://cagcorridorchat.blogspot.com/2008/10/eternity-of-geo-politics.html

———-